Jacques Delors, who died on Wednesday, December 27 at the age of 98 years old, was a genuine socialist, horrified by injustice and eager to make a difference. History will also remember that he was one of the great Christian democrats who made Europe. That was his paradox. In 1985, he was appointed president of the European Commission. He was a passionate, self-made, Christian trade unionist who embodied the golden age of the Commission by paving the way – alongside François Mitterrand and Helmut Kohl – to the euro.

But in France, he was known for his rigor, a "complaining Jeremiah," as Raymond Barre mockingly described him, the indecisive one, who ummed and aahed, before finally deciding not to run for president in 1995. That missed opportunity with the French tortured him. "Either I lied to the country, or I lied to the socialists," he explained, pointing out the gap between his adherence to France's "second left" (a strand of left-wing politics in France in the late '50s and early '60s) and the quasi-revolutionary discourse of the Socialist Party's first secretary at the time, Henri Emmanuelli. But at the end of his life, he told Le Monde: "Sometimes, yes, I regret not having dared to do it. Perhaps I was wrong."

Lost fights and missed opportunities

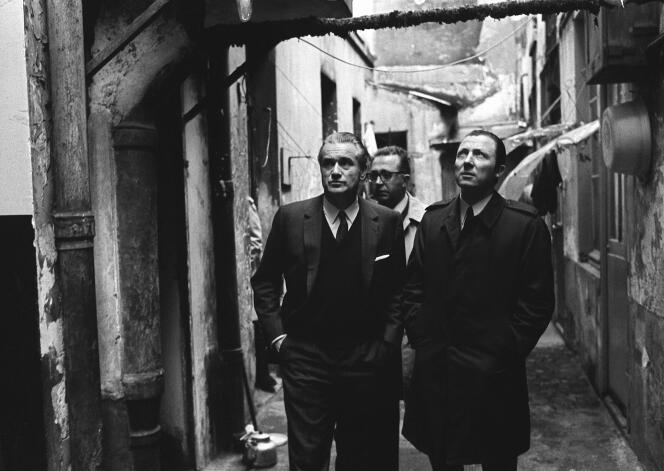

That confession took place in June 2013, on the Rue de Milan in Paris, in the offices of Notre Europe. He created this organization at the encouragement of the German chancellor and the Spanish head of government Felipe Gonzalez when he left Brussels in January 1995, "when Jospin had not done a thing to help me." Jacques Delors such as he was: both happy and unhappy, his voice a little shaky, walking made difficult after several bouts of sciatica, but his eyes a luminous blue that lit up his whole face.

A few days earlier, wearing a pink shirt and red tie, the European activist had gone "to express his anger" at a forum for European progressives being held at the Maison de la Mutualité in Paris – a conference hall where he had received rapturous applause in the past. Urging the EU to speed up the implementation of the growth pact negotiated in 2012 by François Hollande, he asked, "Who is looking after the €120 billion of the European recovery plan?" Then he added, more softly, "Don't worry, we will get there!"

The story he told was full of hope but dotted with lost battles and missed opportunities. There was not an ounce of malice, for while he was uncompromising, it was directed first and foremost towards himself. Neither success nor glory managed to cure Delors of his chronic shyness, of the feeling of being "an old fart" among the political big guns with whom he had rubbed shoulders. The fear of doing badly had been with him all his life, which he drowned in his workaholic attitude. "I lack a quality that is essential for a politician: believing in myself," he said.

Yet he was an only child and was pampered by his parents. Born seven years after the end of the Great War, he had a happy childhood in Paris's Ménilmontant neighborhood, kicking a ball around with his friends whenever he could. He was a sensitive and gifted student and passionate about music and sports. He wanted to be a journalist, a filmmaker, or perhaps even a fashion designer, according to his biographer Gabriel Milesi in his 1985 book Jacques Delors. But when he passed his baccalaureate, his father, Louis, who was a bank messenger at the Banque de France, left him little choice: "There is nothing better than the Banque de France," he told him.

In those days and from that background, you didn't go to university. As a teenager, he did not rebel but worked hard instead. In the evenings, after work, he studied for internal exams, played basketball diligently, set up a movie club, was active in the CFTC union, and lived his life as a young married man. He had met Marie at the bank; she came from the Basque region and had a big heart and a Christian faith as strong as his own. "The most important event of my life," he said. They had two children: Martine in 1950 and Jean-Paul three years later.

Religious commitment

Politically, his heart leant to the left. He admired Pierre Mendès France but hated the games of politics. A year after joining, he slammed the door on the Christian democratic party Mouvement Républicain Populaire (MRP). He felt passionate, however, about what was happening at the CFTC trade union. Three times a week, he lent a hand to those who, alongside the secretary general of the Syndicat Général de l'Education Nationale (SGEN) Paul Vignaux, had worked hard to take religion out of the union. He set up working groups and attracted experts to the journal Reconstruction, where he himself wrote under the pseudonym Roger Jacques.

At the same time, he deepened his religious commitment by getting involved, alongside his wife, in La Vie Nouvelle, a popular education movement that grew out of the Catholic scouts. It was strongly inspired by Emmanuel Mounier's communitarian personalism. When the movement launched the Cahiers Citoyen 60, to develop political, economic and social education for the underprivileged, he naturally became the editor-in-chief.

The trade unions offered Delors the springboard he was missing. In 1959, the CFTC sent him to sit on the Conseil Economique et Social (CES). Three years later, Pierre Massé, impressed by the quality of his work, called him to the Commissariat Général du Plan. This was a decisive turning point: At the age of 37, the self-taught man became a senior civil servant and finally fulfilled his dream of "serving the country." The "plan", under Jacques Massé's ingenious leadership, had reached its height. Jacques Delors saw it as a way of exploring everything he had been dreaming of for the first time. The utopia he aspired to was a more humane society. His method was applying realistic and sensible pragmatism. And his tools were contractual politics – in other words, negotiated compromise between enlightened social groups.

In 1963, the miners' conflict took a turn for the worse. He was appointed rapporteur of the conciliation commission. To try and calm tensions, he invited the trade unionists to dinner at his place. Marie cooked while they looked over the data he had. His report found a 10% wage gap, and the strike was called off. To arrive at this figure, he had to convince the administration and the unions to put their cards on the table. Transparency became his battle. Like the fight against inflation – the damaging effects of which he had just studied – it led to periods of overheating, followed by cooling-off periods, which caused the weakest to suffer the most. To control it, he suggested that wage increases should be fixed in advance, according to the company's results and the economy's performance, instead of being indexed to prices. The idea was not taken up, but it didn't matter; the seeds had been sown.

Six years later, he took up the cause again – but this time, he was at Matignon, the seat of the French government, in the huge office on the first floor where representatives of employers and unions would soon be gathering. He had just been appointed social adviser to the new prime minister, Jacques Chaban-Delmas (1915-2000). "A man from the right!" the left complained. "A man with the desire to change things," Jacques Delors retorted. Chaban-Delmas and Delors met in the early 1960s, when the ambitious president of the Assemblée Nationale surrounded himself with experts from all walks of life. The events of May 1968 convinced them that a "destabilized" society "was ready for reforms." When Jacques Chaban asked for him, he did not need long to think about it. Marie gave him the green light.

Water and fire

His speech on a "new society," delivered at the Assemblée Nationale on September 16, 1969, made history. It drew on the sociologist Michel Crozier's theory of a "blocked society" and offered Delors' idea of contractual politics as a solution. However, the results did not live up to the promises. At the Elysée Palace, Georges Pompidou immediately took umbrage at his prime minister's audacity. The social adviser managed to get EDF to sign a first "progress contract" without the State getting involved. Others followed, but in the summer of 1972, everything came to a halt. Pompidou, fed up, thanked his prime minister. Jacques Delors was sidelined. He was too far to the left for the right, too far to the right for the left. He was shunned.

So he took a step back and created a political organization, Echange et Projets, published a book, Changer ("Change", 1975), and taught for a bit at Université Paris Dauphine after having done so at the elite Paris university ENA. But he was only 47 years old and had acquired a taste for government service. How could he get back into the game? Suddenly, everything started to happen at speed: Georges Pompidou died on April 2, 1974. Jacques Chaban-Delmas immediately declared himself a candidate. Delors helped him, but in vain. Chaban-Delmas was out of the running, while François Mitterrand came very close to victory. From that point on, Delors would move towards him.

Delors and Mitterrand were like chalk and cheese. They first met in the early 1960s in Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber's office at the French newspaper L'Express.

"I need a boy like you," Mitterrand said, trying to win him over. Delors did not respond. It wasn't that he disapproved of the future president's strategy of uniting the left, but he feared his charisma, feared losing his independence, and hated the game of sycophancy. In 1965, he refused to be part of his counter-government. It was the first dispute of many; Mitterrand did not understand Delors's moods and did nothing to spare his feelings. When, in November 1974, the Echange et Projets' founder finally decided to join the Parti Socialiste, he was derided both by CERES, the left wing of the party, and by Michel Rocard's supporters.

What did it matter? Rocard, who he had met in the CFTC and then briefly in the Parti Socialiste Unifié (PSU), was being led astray. The ex-leader of the PSU thought that his time had finally come and that he would be the Socialist candidate for the 1981 presidential elections. It proved to be a fatal mistake. While Delors shared some of his ideas and many of his friends, he didn't like him and considered him unpredictable. The more Rocard got away, the closer Delors got to Mitterrand. In 1978, the day after the legislative elections lost to the left, the two men were seen walking together across the foyer of the Assemblée Nationale. The alliance was sealed. Delors then took an active part in the presidential campaign, seeking to provide reassurance. On May 10, 1981, he was not part of the small handful who stood around the new president at the Hôtel du Vieux Morvan, but he had no doubt: He was going to be part of the adventure.

Kicked up a fuss

He was now a minister, put in charge of the economy and finance, but constrained by Laurent Fabius's budget. Fabius was a close ally of the president, and Delors had no control over him. From the very first day, the franc started to fall. Delors was anxious that the left might not succeed, so he kicked up a fuss and bombarded the Elysée with angry notes. The recovery plan? Too generous. What about fully nationalizing? "Complete nonsense." In November 1981, he was the first to call for a "pause," that fateful word that Leon Blum had used and which had sealed the fate of the Front Populaire.

"You realize what you just said?" Communist Charles Fiterman snarled. But he persisted.

"The time for austerity has come," Delors declared in June 1982, when the franc had just been devalued for the second time.

It was no longer the flourishing cabinet of Delors and Chaban-Delmas, but a killjoy Jacques Delors, who was tense and prone to mood swings, sometimes threw terrible tantrums and often threatened to quit. "I have resigned three times in 38 months," he said, irritated that people might suspect him of lacking the nerve.

At that time, the man was going through a terrible personal ordeal. His son Jean-Paul died of leukemia at the age of 29. A bright boy, he had fulfilled his father's dream of becoming a journalist. The discreet, close-knit family kept the tragedy quiet. The morning of the funeral, Jacques Delors sat in the council of ministers as if nothing had happened, clenching his teeth. Did he have a choice? The most dramatic moment of the term of office was approaching. The supporters of "the other policy" had gone on the offensive. In the evening, they laid siege to Mitterrand to try to get out of the European Monetary System. According to them, it was the only way to revive the economy and escape the German yoke. The minister of the economy resisted hand in hand with the prime minister, Pierre Mauroy. Their European faith brought them together, but it was not enough. Night and day, they mobilized their departments, obtaining figures and graphs that would convince the president that the price to pay for floating the franc would be increased austerity.

In retrospect, Delors and Mauroy were convinced that it was their alliance that won the battle. And yet, they were well and truly rivals during those dramatic days when everything wavered. When, at the end of March 1983, Mitterrand considered moving away from Mauroy, he invited Delors, Fabius and Pierre Bérégovoy to lunch to put them in competition. At the end of the lunch, he had his sights set on Delors, offering him the keys to Matignon, but the man in question committed a great sin of pride: He wanted to be appointed, but on the condition that he would also have control of monetary policy, like Raymond Barre had done under Valéry Giscard d'Estaing. "I cannot accept that," answered François Mitterrand, who kept Jacques Mauroy in the end.

Crisis as teaching tool

Delors would never be prime minister. And afterwards, of course, he would regret it. But while his chances on the national scene were fading, his star was rising across the Rhine. Annoyed at having to constantly rescue the franc, the Germans learned to appreciate the sensible Frenchman, who embodied a ruthless sense of rigor.

In the aftermath of the dramatic days of March 1983, Delors launched the compulsory loan, the "carnet des changes" (a way of limiting holidaymakers' access to foreign currency), and a levy of 1% on all income. He wanted to shock with the truth, use the crisis as a teaching tool, and push the French to take on the reforms. He met with journalists every week and, despite the bitter pill he was making his country swallow, his popularity grew. He took the opportunity to continue his fight against inflation, with the de-indexation of wages on prices – a revolution he had developed in the early 1960s. Helmut Kohl was watching it all closely. When, in 1985, the presidency of the Commission of the European Communities became vacant, the Chancellor offered Delors his crucial support. Mitterrand backed Claude Cheysson, the Quai d'Orsay's favorite.

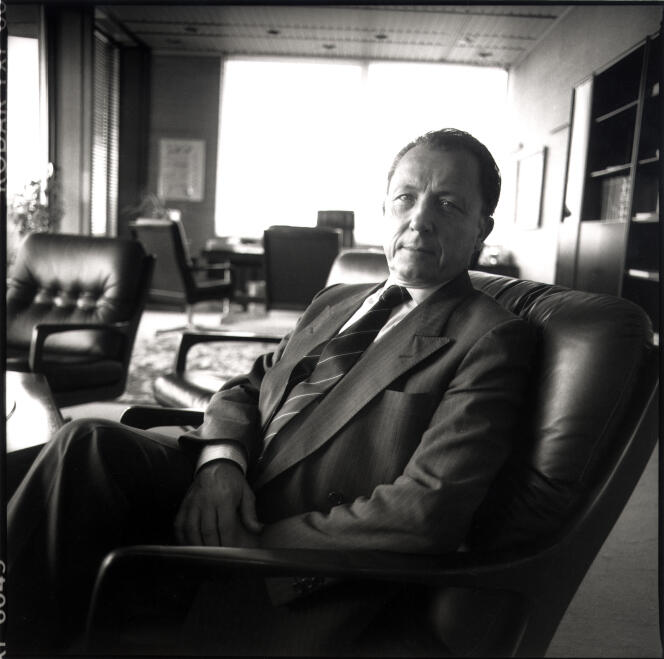

Jacques Delors, who at the age of 59 left the national scene to settle in Brussels with his wife, remained a tormented character. He was not satisfied with his record as a minister. Mitterrand was wary of the tax reform he had designed to increase competitiveness. But this time, the self-taught man had the rank of head of state and cooperation was going to be much more fruitful. Delors saw the phenomenon of globalization emerging. "The only choice Europe has is between survival and decline," he warned upon taking office.

In June 1984, the Fontainebleau Summit put an end to a series of disputes – notably with Britain – which were poisoning the lives of the 10 member states. So he went ahead and toured the European capitals to test three ideas: a common currency, a common defense, and the democratization of institutions. None of these ideas were met with unanimous approval, so he fell back on the idea of a common area without borders, as well as the free movement of goods and people. Was this putting the economy before politics? It was the same approach and the same strategy as the founding fathers: the idea of the spiral; each decision made called for another one that made it impossible to go back.

Two laws defined his 10-year presidency: the Single Act, signed by 12 countries in 1986, which opened the way to the single market; and the Maastricht Treaty, in December 1991, which created the monetary union. These two laws were decisive for European integration and marked the golden age of a community-based approach. Initiate, execute. Jacques Delors defended the Commission's plan tooth and nail to Europe's heads of state. This was the only way, he said, to overcome national egoisms.

In 1989, the fall of the Berlin Wall turned everything upside down and unbalanced the Franco-German dynamic. The president of the Commission did not put a foot wrong. He immediately supported reunification, unblocked aid, once again attracted the good graces of the Chancellor and cleared the way for a great monetary deal. Mitterrand accepted reunification and Kohl resigned himself to sacrificing the mark by January 1, 1999 at the latest. The majority of Germans, however, were against it.

The advent of the single currency marked the height of the trio's power – but also the beginning of doubts. The "no" vote in the Danish referendum and the passionate debates in France on the Maastricht Treaty highlighted the lack of democracy and the shortcomings of a social Europe. Later, it would be the backdrop to the monetary union that would worry Delors: "No single currency without coordination of economic policies," he warned. The French turned a deaf ear. The expansion of Europe and the loss of efficiency in the decisions it made marked a new challenge. At the end of his mandate, in December 1993, Delors published a White Paper on competitiveness and employment. It was a sort of testament in which he pointed out the weaknesses of the European economy: massive unemployment and insufficient competitiveness. The member states refused to loosen their purse strings to invest.

The providential man

In January 1995, heads of state, civil servants, employers and trade unionists gathered to applaud the man who had changed the face of Europe. He didn't join in with the triumph. He was unable to enjoy it, as if he sensed what was to come: loneliness in Paris, without even an office to go back to. But whose fault was that?

A few months earlier, he was the providential man, the one who was going to extricate the left from waning Mitterrandism. The so-called "transcourants" (those who sought to overcome internal divisions) in the Parti Socialiste wanted him as a candidate for the 1995 presidential election. Jacques Delors was ready to play the game. The political think tank, Club Témoin, which he supported, had flourished. François Hollande was at the forefront. Things were starting to come together, even more so on the day Henri Emmanuelli, the first secretary of the Parti Socialiste, also started to bait the "Brussels man." In the fall of 1994, Delors published L'Unité d'un homme ("Unity of a Man"). The book was snapped up as if the whole of France was overcome with a fanaticism for him. But on December 11, the bubble burst. At the end of a long televised interview with Anne Sinclair, he announced that he would not stand as a candidate. The socialists felt betrayed. Mitterrand, though, was hardly surprised.

The man who was afraid of getting his hands dirty gave up the limelight, both relieved and frustrated. He continued to carry out a lot of work for UNESCO, the CERC (Conseil de l’Emploi, des Revenus et de la Cohésion Sociale) and Notre Europe, but with a sense of sadness at not having made the most of his gifts. At the end of his life, he was angry at the Socialists for "having marginalized him from the start" and at François Fillon "for having let the CERC die without bothering to explain why." He was upset that, in April 2013, during the ceremonies for the 50th anniversary of the Elysée Treaty, not a single Frenchman mentioned his name, "unlike the Germans." And he still couldn't believe that, in 2001, Lionel Jospin chose Valéry Giscard d'Estaing to chair the Convention on Europe, from which the constitutional treaty would emerge.

However, he chased away his bitter feelings as quickly as they came. Wherever he was, Jacques Delors "served" and that was his most noble mission. As a preface to his memoirs, he chose these words, which were not his own: "The world is divided into two: those who want to be someone and those who want to achieve something." It said everything about him.